Men stand next to blood stains and charred remains inside a home where witnesses say Afghans were killed by a U.S. soldier in Panjwai, Kandahar province south of Kabul, Afghanistan in 2012 Allauddin Khan AP

An Army court will decide this week whether to review and perhaps reduce the life sentence of a soldier who massacred Afghan civilians — and in the process it will judge a controversial malaria drug given to troops that is known to cause hallucinations, anxiety and paranoia.

The prescription was not considered during the investigation and his legal team will use this as the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals weighs whether Bales is entitled to a new sentencing hearing on two procedural issues – whether the prosecution failed to disclose evidence related to his case and that the court failed to investigate a military judge’s disclosure of protected information.

Mefloquine is a malaria treatment medication that was commonly used by the U.S. military as a prophylactic in malaria endemic regions, taken once a week by troops. It has been controversial since its commercial introduction in 1989, as it is known to cause neurological and vestibular problems in a small percentage of users.

Concerns inside the Defense Department began surfacing in 2002 following a string of violent deaths and suicides among soldiers and military family members at Fort Bragg, N.C. In 2004, a federal investigation found that 11 troops taking the medication experienced debilitating vertigo.

In 2009, the Defense Department issued a policy listing it as a last-choice preventive, to be used only in areas where strains are resistant to other medications.

And in 2012 and 2016, several case studies were published of troops developing brain damage as a result of taking the drug.

Shortly after Bales murdered the Afghan civilians on March 11, 2012, retired Army psychiatrist Col. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie raised questions as to whether Bales had been taking mefloquine during his deployment or on his previous three trips to Iraq.

The next month, in April 2012, the Food and Drug Administration received notification from Roche, the maker of the brand-name version of mefloquine, that it had received a report from an anonymous pharmacist that a patient taking the medication had developed homicidal behavior that “led to the homicide killing of 17 Afghans.” (Initial reports cited that 17, not 16, villagers had been killed.)

“It was reported that the patient was suffering from traumatic brain injury and was administered mefloquine in direct contradiction to U.S. military rules that mefloquine should not be given to soldiers who had suffered traumatic brain injury due to its propensity to cross blood-brain barriers inciting psychotic, homicidal or suicidal behavior,” the report stated.

Bales had sustained a traumatic brain injury during his last deployment to Iraq in 2009.

The FDA disclosed the adverse report in 2013 as Bales was being sentenced, having pleaded guilty in exchange for dropping the death penalty. A lead prosecutor in the case, now-retired Army Lt. Col. Jay Morse, told the Seattle Times last week that the document was not considered to be evidence that Bales used the drug and no other documentation was available on Bales’ prescription history.

“There is zero evidence that Bales was on mefloquine,” Morse said. The Seattle Times first reported Bales’ legal team’s plan for the sentence review.

But to any member of the U.S. military who has deployed, the lack of evidence or record is not surprising. In January 2012, then Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs Dr. Jonathan Woodson issued a memo noting that some deployed service members were issued mefloquine without it being recorded in their medical records.

“In addition, not all individuals have been provided the required mefloquine medication guide and wallet information card. It is incumbent upon us to ensure our service members are appropriately screened and informed about the medicines they are taking and we must accurately record their prescriptions in their medical record,” Woodson wrote.

The FDA in 2013 placed a black box warning on mefloquine, to alert patients of the drug’s potential neurological and psychiatric side effects.

Bales attorneys have retained mefloquine researcher and former Army public health physician Dr. Remington Nevin as a subject matter expert on the case.

In his clemency request in 2014, Bales cited post-traumatic stress disorder, his brain injury, alcohol and steroid use while deployed, as well as his reliance on sleeping pills and steroids he took as possible contributing factors.

He also spoke of guilt, fear and the desire to protect his fellow soldiers all as factors.

“I still don’t believe that the PTSD, TBI, alcohol, steroids and sleeping pills were the only factors in my actions on March 11, 2012. I believe there is much more,” he wrote.

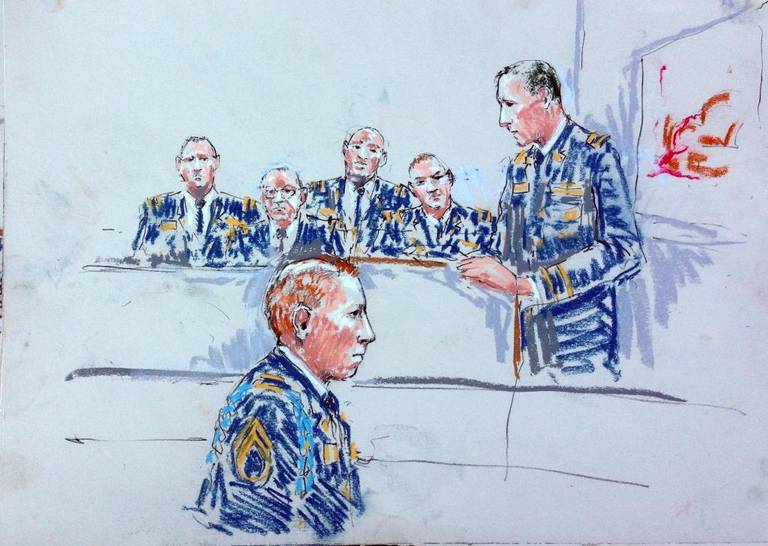

In this courtroom sketch Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, foreground, is seated as prosecutor Lt Col. Jay Morse, right, speaks to the jury in a courtroom at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Wash. during a sentencing hearing in the slayings of 16 civilians killed during pre-dawn raids on two villages on March 11, 2012. Peter Millett AP