EARLY IN THE morning of March 11, 2012, Army staff sergeant Robert Bales left his remote outpost in an impoverished region of Kandahar Province, Afghanistan and killed 16 people in two nearby villages. His victims, mostly women and children, were sleeping at the time. Bales shot or stabbed them to death before dragging some of their bodies into a pile and lighting them on fire.

His crime is as baffling as it is gruesome. In June, he pleaded guilty to the murders in a military court, telling the presiding judge: “There’s not a good reason in this world for why I did the horrible things I did.”

In the weeks since his guilty plea, there’s been growing speculation that a drug meant to prevent malaria may have played a role in the murders. In certain circles, including the military, the Peace Corps, and other organizations that send people into malarial zones for long periods of time, the drug – known as mefloquine – has long had a bad reputation for setting nerves on edge and causing nightmares.

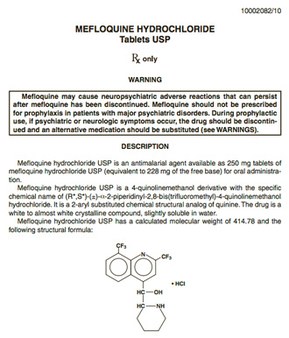

In some cases, mefloquine can mess with the mind in more serious ways, causing confusion, hallucinations, and paranoia. On July 29, the FDA added a black box – its strongest warning – to the label of the drug, citing neurological and psychiatric side effects that can last months or years after someone stops taking it.

“I like to say this drug is like a horror show in a pill,” said Remington Nevin, a former Army physician who’s now an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University. In a recent paper, Nevin argues that the drug’s effects on the brain and behavior make it likely to become increasingly important in forensic psychiatry.

Although mefloquine has been eyed as a possible contributing factor in previous killings, so far apparently no one has argued successfully in court that the drug made someone less culpable for a crime.

Bales’s defense team did not raise the issue during his trial, but they still could do so at his sentencing hearing on August 19. “If it’s seen as mitigating in the Bales case, I could certainly see this coming up in a lot of cases where people might say ‘mefloquine made me do it,'” said Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, a former Army psychiatrist and a coauthor with Nevin on the recent paper.

A Troubled Past —————

Mefloquine is a puzzling drug with an unusual history.

It was discovered by the U.S. Army during the Vietnam war. The military realized that in many parts of the world, the malaria parasite was evolving resistance to a drug called chloroquine, which was the standard antimalaria drug of the time.

Mefloquine was identified from a pool of more than 250,000 compounds screened for their ability to stop these chloroquine-resistant malaria strains, according to a 2007 paper by British physician Ashley Croft. The drug had the added advantage of requiring just one dose a week instead of one a day. The Army handed off the compound to F. Hofmann-La Roche, which gained FDA approval for the drug in 1989 and marketed it under the trade name Lariam. “The underpinning safety and pharmacokinetic studies which should have been performed prior to the licensing of Lariam … were never carried out,” Croft wrote.

When the first careful clinical trials to assess how well the drug is tolerated by healthy people were finally reported 12 years later, they turned up evidence of common neuropsychiatric side effects, including strange or vivid dreams, insomnia, dizziness, and anxiety. Croft speculates that the FDA would not have approved the drug if the results of those trials had been available before 1989.

In the intervening years, anecdotal evidence that the drug can have devastating consequences has piled up.

A smattering of case reports have linked the drug to suicide. In one particularly horrible example, a 27-year-old man with no prior history of mental illness committed suicide by stabbing himself in the head and torso with a knife. A recent investigative report by the Irish broadcaster RTÉ implicated mefloquine in a cluster of suicides among Irish Defense Forces deployed on peacekeeping missions.

Perhaps most famously, the drug was investigated as a contributing factor in the murder-suicides at Fort Bragg in 2002, when four soldiers, three of whom had recently returned from Afghanistan, killed their wives, and two of them killed themselves. (A military panel concluded that mefloquine was an unlikely factor in the killings, instead placing the blame on marital problems and the stress of deployment.)

Nevin and Ritchie both say they saw the drug’s effects during their time in the military. Ritchie served in Somalia. “I think it was my first day there, a young man was evacuated out of there screaming and yelling, and it was found that he’d taken five mefloquine tablets,” she said. “He was supposed to be taking them once a week and he took them once a day.”

In Afghanistan, Nevin says the drug took a toll on his unit in more subtle ways. “Even though everyone may not become clinically ill, the bell curve for anxiety, irritability, and restless sleep is going to shift, and that can have dramatic effects on a unit,” Nevin said. “We were being affected by the drug.”

Perhaps more disturbingly, mefloquine was sometimes given out indiscriminately.

Nevin says that before he deployed to Afghanistan in early 2007, he saw medics at Fort Bragg distributing the drug from plastic trash bags. “We were told to reach into a garbage bag and find our prescription, but if we couldn’t find it, to just take someone else’s,” he said. That would have violated the military’s policy at the time, which required screening for psychiatric problems and previous traumatic brain injuries – and excluding soldiers who tested positive from getting mefloquine.

A study Nevin published in 2008 found that nearly 10 percent of 11,725 active-duty personnel in Afghanistan had either a pre-existing condition or were on other medication that should have barred them from taking mefloquine. A follow-up study found that 14 percent of those who should not have taken mefloquine received a prescription for it.

In recent years, the U.S. military has significantly called back its use of the drug. A recent set of recommendations, issued in April, advise the use of mefloquine only in patients who are unable to tolerate two other antimalarial drugs and have no recent history of TBI or psychiatric problems.

Mysterious Biology ——————

Kim Pierro /FLICKR

What mefloquine does to the brain is poorly understood.

The drug’s chemistry predisposes it to build up in fatty tissues like the brain at much higher concentrations than it does in the bloodstream, where the malaria parasite hangs out. “Mefloquine is a psychotropic drug with incidental anti-malarial properties,” Nevin said.

One thing mefloquine does in the brain is block tiny molecular pores called gap junctions. Gap junctions help neurons synchronize their electrical activity by allowing ions to flow freely between them. One hypothesis, Nevin says, is that mefloquine desynchronizes neurons that normally put a brake on the limbic system, an evolutionarily ancient network of brain regions important for memory and emotion.

Cutting the brakes on the limbic system, he says, could be how the drug produces symptoms like anxiety, paranoia, and hallucinations.

It’s a plausible scenario, says neuroscientist Michael Fanselow of UCLA. “Gap junctions regulate activity in two very key limbic structures, the hippocampus and amygdala,” Fanselow said. The hippocampus is involved in memory and navigation, and disrupting these functions could result in disorientation and hallucinations. Disrupting the amygdala, meanwhile, could produce anxiety or alter emotional reactions, Fanselow says.

Nevin thinks it’s also possible that mefloquine, or perhaps some byproduct produced as the drug gets broken down in the brain, is directly toxic to neurons. Doses comparable to those given to people disrupted the sleep and balance of rats and killed neurons in the animals’ brain stems, according to a 2006 study.

Problems with sleep and balance are among the most common long-term neurological side effects reported for mefloquine. However, the kind of damage seen in the rats could only be seen in humans by doing an autopsy and looking at brain tissue under a microscope. That’s never been done, Nevin says.

“If this sort of damage were apparent on MRI [scans] we would have figured this out a long time ago,” he said.

Defensive Maneuvers ——————-

Could mefloquine really cause someone to commit an atrocious act like the murders Bales committed?

Probably not on its own. After all, thousands of travelers have taken mefloquine and experienced little more than bad dreams and a touch of jumpiness. But the drug’s effects might be amplified in soldiers living with the daily stress of combat, or who’ve experienced traumatic brain injuries from explosive blasts – the signature health hazards of the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“I think mefloquine is more like the straw that breaks the camel’s back when there’s other things going on,” Ritchie said.

Robert Bales definitely had other things going on. He admitted to the court that he’d been taking anabolic steroids, and fellow soldiers testified during his trial that they’d been drinking alcohol against regulations on the night of the murders.

Whether he was also taking mefloquine at the time is not clear.

In July, Bales’s defense attorney, John Henry Browne, told the Seattle Times that Bales took mefloquine in Iraq, where he did three previous tours of duty (and also where he also reportedly suffered a TBI, which should have disqualified him from receiving any more of the drug).

A document Nevin obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request hints at the possibility Bales took the drug during his fateful final tour in Afghanistan as well. The document, an “adverse event record” sent to Roche, does not name Bales but involves a soldier who took mefloquine and killed 17 Afghan civilians, the same erroneous number listed in Bales’s original charging documents.

However, Nevin has not been able to determine who filed the adverse event report. It’s possible that whoever filed it had no direct knowledge of Bales’s case. Browne, the defense attorney, told the Seattle Times that he does not know whether Bales took mefloquine in Afghanistan because his medical records are incomplete.

The new black box warning.

IMAGE: FDA

The drug is detectable in the blood for up to a month, but the Army has not said whether Bales was tested.

If evidence comes to light that Bales was on mefloquine at the time of the murders, that could be viewed as mitigating evidence at his sentencing hearing, says Christopher Slobogin, a professor of criminal law and psychiatry at Vanderbilt University. The relevant legal principle is called involuntary intoxication. That doesn’t mean someone had a good buzz going, Slobogin explains, it means that they took a drug – either unknowingly or unaware of the possible side effects – that caused a serious cognitive impairment.

“The classic example is someone slipping LSD in your coffee,” Slobogin said. “It implies an inability to appreciate what one is doing or to appreciate the wrongness of what one is doing.”

The recent FDA announcement, which cites psychiatric side effects lasting months or years, could aid the defense as well, especially if it only has evidence that he took mefloquine during his previous tours in Iraq and can’t prove he was taking it at the time of the crime. “That’s obviously helpful to the defense,” Slobogin said.

“The accused is given considerable leeway during the sentencing phase to present evidence of extenuation and mitigation,” said William Woodruff, a law professor at Campbell University in Raleigh, N.C., and former colonel in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps. It seems likely that the court would admit evidence about mefloquine at the sentencing hearing, Woodruff says, but how much weight they would give it is difficult to predict.

On August 19, a military jury will convene to decide Bales’s fate. His guilty plea takes the death penalty off the table. The question is whether his life sentence will include any possibility of parole.

No matter what the jury decides, we will probably never know exactly what role, if any, mefloquine played in this horrific crime. And as long as the drug is in use, it’s unlikely to be the last time we’re left to wonder.